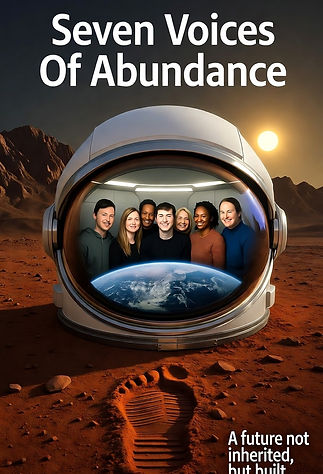

The Seven Voices Of Abundance

Follow the experiences of seven individuals who live in 2045 and see what the future could hold for mankind

2045 Cultural Archive

Copyright © 2025 by Dan Diotte All rights reserved.

No portion of this book may be reproduced in any form without written permission from.

the publisher or author, except as permitted by U.S. copyright law.

Contents

Prologue

1. The Family

2. The Businessman

3. The Environmentalist

4. The Educator/Student

5. The Artist/Creator

6. The Doctor/Healer

7. The Explorer

Epilogue

Prologue The Weight of Memory

Listen to the Audiobook of the Prologue

The recycler hums its quiet morning song in my kitchen, a sound my grandmother would have mistaken for a broken dishwasher. I pause in writing these words to listen: that low, contented purr of plastic breaking down into base polymers, ready to become whatever my family needs today. My daughter's outgrown shoes from last night are already becoming the raw material that one day might be recycled into her younger brother's art project.

This sound didn't exist in 2019.

Neither did the gentle whir of our home's fabricator, currently printing replacement handles for the cabinet doors my son somehow managed to break while "testing their structural integrity." The maple-scented PLA will be ready in twenty minutes, perfectly matched to our kitchen's wood grain because the house AI remembered the pattern from when we first moved in.

I set down my stylus, itself printed just yesterday when my old one finally gave up, and walk to the window. Below, the morning commute looks nothing like the gridlocked nightmare I once knew. A few people emerge from the underground transit hub, having traveled here from Seoul, Lagos, or São Paulo in the time it used to take me to drive across town. Their faces carry that particular mix of wonder and casual acceptance that still marks my generation, the Transition Generation, as the historians call us.

We remember the weight of scarcity like a phantom limb.

Let me tell you what that weight felt like, because if you're reading this in 2055 or beyond, you might think abundance was always our birthright.

I remember standing in a grocery store in March 2020, staring at shelves stripped bare by panic. Not just toilet paper, though that became the absurd symbol of our fear. But flour, rice, canned goods, cleaning supplies. The fluorescent lights buzzed overhead, illuminating nothing but empty metal and the hollow echo of our footsteps. A woman next to me was crying quietly, not from embarrassment, but from the bone-deep terror that there might not be enough.

That's what scarcity felt like: the constant, gnawing anxiety that there might not be enough. Enough food, enough money, enough time, enough planet left for our children.

I remember the arithmetic of survival that governed every decision: Could we afford to fix the washing machine or would we hand-wash clothes for another month? Should I take that promotion that meant sixty-hour weeks, or stay present for my children's childhood? Did we dare take a vacation when the polar ice caps were melting and the wildfire season now lasted eight months?

Every choice carried the weight of what we couldn't have.

The sound that changed everything wasn't dramatic. It wasn't the roar of rockets or the fanfare of a political announcement. It was the quiet hum of Chen Martinez's household recycler on a Tuesday morning in October 2031.

Chen lived three houses down from me then, in the old neighborhood where we still thought recycling meant sorting plastic bottles into blue bins and hoping someone, somewhere, would actually process them. He'd been selected for HingeCraft's pilot program—something about automated household manufacturing that we neighbors discussed with the polite skepticism reserved for flying cars and jetpacks.

I was walking my dog when I heard it: a sound like a contented cat purring, emanating from Chen's garage. Through the open door, I could see him and his eight-year-old daughter Maya standing over a white box about the size of a dishwasher. Maya was holding what looked like a broken toy, one of those expensive remote-control helicopters that parents buy in guilt and children break within hours.

"Just put it in the input tray," Chen was saying, his voice carrying a note of wonder I'd never heard from him before. He was an accountant, methodical and practical to his core. Wonder wasn't his default setting.

Maya dropped the broken helicopter into a slot on top of the machine. The purring grew slightly louder.

"How long?" she asked, bouncing on her toes.

"The AI says forty-three minutes for a new one," Chen replied. "Want to watch?"

Through the machine's transparent side panel, I could see the helicopter dissolving, not violently, but gently, like sugar in warm tea. The plastic components separated into their base elements while tiny robotic arms sorted and moved the salvaged electronics to a separate tray.

I stood there for the full forty-three minutes, my dog growing increasingly impatient with my stillness. I watched that machine consume broken plastic and birth new possibility. When the process finished, Maya pulled out a helicopter identical to the one she'd broken. No, not identical. Better. The new design had incorporated subtle improvements: more efficient rotors, a sturdier frame, softer edges.

"It learned from what went wrong," Chen explained, noticing my fascination. "The AI analyzed the break pattern and fixed the weak points."

Maya launched her new helicopter into the October sky, and I felt something shift in my chest. Not hope, hope was too small a word. This was recognition. Recognition that the arithmetic of scarcity, which had governed every decision of my adult life, had just become obsolete.

That was fourteen years ago. The children who broke toys that morning are now in their twenties, designing solutions to problems we never imagined could be solved. Maya Martinez, that eight-year-old who fed a broken helicopter to a machine that sang back with abundance, now leads a team of engineers building atmospheric processors for Mars colonies. She's never known the weight of scarcity because she grew up in a world where broken things became better things.

But the transition wasn't instant or effortless. There were the Resistance Years from 2033 to 2036, when old-economy interests tried to legislate abundance out of existence. I remember the Corporate Wars of 2034, when manufacturing giants attempted to sabotage the PET supply chain, only to discover that communities had already learned to break down ocean plastic into feedstock. There were the Identity Crises that followed. Millions of people suddenly freed from jobs that had defined them, struggling to discover who they were when survival was guaranteed.

Some adapted by 2037. Others took until 2041. A few never did.

I think about Elena Vasquez sometimes. My neighbor two streets over who kept an "emergency stockpile" in her basement until she died in 2043. Canned goods from 2031, water purification tablets, batteries for devices that no longer existed. She couldn't believe abundance would last, couldn't trust that there would always be enough. The psychology of scarcity had roots too deep for even a transformed world to easily extract.

Which brings me to why I'm writing this now, in the spring of 2045, fifteen years after abundance became our new normal.

Last month, I was appointed as the Oral History Curator for the North American Cultural Archive, a role that wouldn't have existed in the old world, because we were too busy surviving to document our living. My first project is this collection: seven voices from different walks of life, each telling their piece of the story of how our world was reborn.

These aren't politicians or CEOs, though their decisions mattered. These aren't the inventors or theorists, though their innovations made it possible. These are ordinary people who lived through extraordinary change, who woke up one day to discover that the rules of reality had fundamentally shifted.

I've chosen seven storytellers whose experiences weave together like threads in a tapestry:

Margaret Chen-Williams (no relation to my neighbor Chen, though she loves when people ask), a mother of three who watched her family's daily rhythm transform from survival logistics to creative play. She'll tell you what it felt like when printing her daughter's shoes for the first time shifted from miracle to Tuesday morning routine.

David Okafor, a former corporate vice president who lost his job in the Management Collapse of 2034 and found his calling designing artisanal woodworking templates that now ship globally through underground freight in minutes. He'll explain how work didn't disappear, it was reborn as passion made practical.

Dr. Amara Patel, the marine biologist who documented both the death and resurrection of coral reefs, who can tell you the exact moment she knew the Earth was healing and why she wept into her diving mask when she saw colors returning to bleached coral.

Jin Watanabe, now thirty-one, who was in high school when AI tutors first appeared in classrooms and who designed their first telescope at age sixteen. They'll show you how education evolved from information transfer to curiosity cultivation.

Zara Al-Rashid, whose fashion designs went from rejection letters to global adoption in a single day, who learned to collaborate with AI as co-creator rather than competitor. She'll demonstrate how creativity multiplied when tools became infinite.

Dr. Michael Running Bear, the physician who performed the last major surgery by hand in 2039 before AI-assisted robotics made human error obsolete, yet found that healing became more human, not less, when technology handled the technical aspects.

And Lieutenant Commander Sofia Restrepo, former military pilot, current Director of Interplanetary Transit, who took the first commercial underground train from Bogotá to Bangkok in 2038 and later commanded humanity's first permanent settlement beyond Earth. She'll trace the path from a world divided by borders to a species expanding across solar systems.

As I've conducted these interviews over the past six months, certain questions keep surfacing, questions I hope this collection will help answer, or at least illuminate:

How did we avoid the collapse that seemed inevitable? When abundance replaced scarcity as the organizing principle of civilization, why didn't we tear ourselves apart fighting over new forms of power? What prevented the chaos that economists and politicians predicted when traditional work disappeared and traditional wealth became meaningless?

More importantly: What ensures this transformation endures? How do we teach children who've never known ‘want’ to value what they have? How do we maintain the innovation and creativity that abundance enables without sliding into complacency?

And perhaps most critically: Was this transformation inevitable once the technology emerged, or was it a choice, a collective decision to believe in abundance and share it rather than hoard it?

I think about Elena Vasquez's basement stockpile and wonder: Are we one crisis away from returning to scarcity thinking? Or have we truly evolved beyond the psychology of not-enough?

***

The recycler has finished its morning work. I can hear my children stirring upstairs—my daughter Sofia (named for the commander, though she was born before we met) planning her day in the maker lab, my son Marcus already asking the house AI about the structural properties of different polymers for his art project.

They've never known the weight of empty shelves or the arithmetic of survival. For them, abundance isn't miraculous, it's simply how the world works. When something breaks, you feed it to the recycler and it becomes something new. When you need something that doesn't exist, you design it and print it. When you want to visit friends on another continent, you take the underground and arrive in time for lunch.

This is both humanity's greatest achievement and its greatest vulnerability: a generation that has never been forced to choose between possibilities because all possibilities are available.

In the interviews that follow, you'll hear seven different perspectives on this transformation, seven different answers to the question of how we got here and where we're going. Some will surprise you. Some will challenge assumptions you didn't know you had. All will remind you that the future isn't something that happens to us, it's something we choose, moment by moment, decision by decision.

The recycler hums. The fabricator whirs. Somewhere in Seoul, Lagos, and São Paulo, people are waking up to abundance they still remember earning.

Perhaps the greatest invention wasn't the hinge, or the printer, or even the AI. It was our choice to believe in abundance, and to share it.

Listen now, as seven voices tell the story of how our world was reborn.

Chapter 1 - The Family (Margaret)

Audio Book

Listen to Chapter 1

Chapter 1 – The Family (Margaret)

Interview with Margaret Chen-Williams, recorded March 17, 2045, for the North American Cultural Archive.

Interviewer: “Margaret, when you think back to the years before abundance, what do you remember most clearly? What did scarcity feel like inside your home?”

I still remember the kitchen lights still humming, the old fluorescents buzzing faintly over a stack of unpaid bills. It was 4:07 a.m., and I had just returned from another night shift at the hospital. My husband David had fallen asleep at the table, pen still in his hand, half-finished arithmetic scratched onto the paper: mortgage due, utilities late, grocery money short. A pot of coffee sat cooling between us, untouched. The smell had gone bitter. I remember thinking, we’re drowning, and I can’t swim fast enough.

That was the rhythm of life then. Work, collapse, scrape together enough energy to parent, and repeat. My body was always tired, my mind always racing. My children were growing up in snatches, five-minute conversations at the door, homework checked in stolen moments, birthdays reduced to budget math. I loved them fiercely, but every choice I made felt like a subtraction: of time, of money, of joy.

Interviewer: “Would you say scarcity defined you as much as it defined your circumstances?”

“Scarcity wasn’t just numbers in a bank account, it was the air we breathed. It was the phantom limb of every decision.”

You know, It was Emma who brought the miracle home. She was ten then, fretting about her school picture day. Her sandals had split down the side, and payday was still three days away. I tried to smile, to tell her we’d make do, but the truth sat heavy: she would stand in front of her classmates in shoes that marked her as less. Children notice these things, even if adults pretend not to.

David had heard about the new HingeCraft recycler at the community center, the pilot model everyone was whispering about. Skepticism colored his voice when he suggested we try it. I remember clutching Emma’s broken sandals, hesitating before sliding them into the input tray. The machine purred to life, a sound I hadn’t learned to trust yet.

Emma looked up at me, eyes wide. “Will they really fit?” she asked. My throat tightened. “The AI measured your feet, sweetheart,” I whispered, praying I wasn’t lying.

Forty minutes later, she held the new pair, same color, same design, but sturdier. She slipped them on, wiggled her toes, and squealed with delight. I sank into a chair and wept. Not because they were shoes, but because for the first time in years, the world had given instead of taken.

That was the day that survival’s arithmetic shifted into something else. HingeCraft answered a prayer that scarcity would never allow me to voice aloud.

Interviewer: “So that moment became your turning point?”

It was the first time I realized we didn’t have to ration hope.

The machines multiplied quickly after that. A household HingeCraft fabricator humming in the corner, a garden AI regulating soil nutrients, a quiet robot vacuuming underfoot. Meals planned themselves, laundry cycled automatically, chores evaporated into silence.

But inside me, resistance coiled. I found myself scrubbing counters already spotless, folding laundry that no longer needed folding, hovering over robots as if my supervision mattered. When David caught me re-cleaning the kitchen, he laid a hand on my shoulder. “You don’t have to manage everything anymore, Margaret.”

I bristled. If I wasn’t managing, what was I? For so long, exhaustion had been my identity. Rest felt suspicious, indulgent.

It took months before I discovered clay. One afternoon, while the robots hummed and the children played, I sat down at a pottery wheel in the mall’s HingeCraft-sponsored maker-space David had started coordinating. My hands sank into cool earth, shaping something that was mine alone. Not survival. Not necessity. Creation. That was the beginning of a new rhythm.

Interviewer: “Would you say letting go of control was the hardest part?”

Yes, abundance gave me time, but it also forced me to face myself without excuses. But there were more surprises, Emma’s birthday that year was unlike any before. We gathered at the cultural-tech mall, its atrium glittering with light and possibility. Children designed their own decorations on shared tablets, printing streamers that shimmered like shifting rainbows. Parents exchanged HingeCraft design templates instead of shopping bags, laughing at how little money mattered when creativity became the currency.

I remembered the years of $200 birthdays, balloons, store-bought cakes, rented party rooms, all meant to prove love through receipts. Now love shone in collaborative invention. Emma’s smile as her friends unveiled the decorations they’d designed for her, custom, thoughtful, impossible under the old system, was brighter than any candle.

Status had shifted. Not who could spend the most, but who could imagine the most.

Interviewer: “And you? How did that shift feel to you?”

She answered without hesitation: “Like I’d been holding my breath for years, and someone finally let me exhale.”

Yet abundance did not erase fear overnight. For months, I kept a secret. In the basement, tucked behind boxes, I stockpiled cans of beans and rice, bottled water, and cleaning supplies. Old habits gnawed at me. What if it stops working? What if the recycler breaks? What if this is all temporary?

The day David found the stash, he didn’t scold. He simply picked up a dusty can, turned it in his hands, and set it back gently. “It’s hard to let go of survival mode,” he said softly. “But we can’t carry scarcity into abundance and expect it not to weigh us down.”

He pointed toward the hum of the HingeCraft recycler upstairs. “That thing has rebuilt half our house already, Margaret. It’s not going away.”

I wanted to believe him. Slowly, I did. The cans dwindled, the basement emptied, but the phantom limb of scarcity never vanished entirely. I suspect it never will.

Interviewer: “So even in abundance, fear lingered?”

Fear leaves an imprint, but abundance gives us tools to live without obeying it.

The ones who never carried that weight, my children, became my teachers. Marcus, only six, tugged at my hand one afternoon as I hesitated over a broken chair. “Mom, why do you always ask ‘can we?’” he asked. His small fingers traced the chair’s cracked edge. “Just feed it to the recycler and see what it becomes.”

It was a HingeCraft recycler, of course, humming steadily in the corner of the living room. Marcus didn’t even think twice about it. To him, possibility was the default. Scarcity was a story adults told, not a law of nature. Emma and her siblings designed toys, clothes, even furniture with the ease of breathing. Their laughter filled the house with a kind of freedom I hadn’t known as a child. They lived in a world where the question wasn’t “can we afford this?” but “what do we want to make today?”

Interviewer: “Do you envy them for never knowing the weight you carried?”

She shook her head. Not envy. Relief. They don’t have to learn how to breathe. For example, now, years later, we sit together at the dinner table, a memory wall casting gentle images of the day’s highlights across the room. Marcus proudly shows off the art project he printed that morning, Emma scrolls through HingeCraft collaborations with her friends, and David shares updates from the maker-space.

I watch them, heart swelling with gratitude and a flicker of fear. We’re not managing survival anymore. We’re curating joy. But in quiet moments, I wonder: what happens when these children face real problems? Problems you can’t solve with a recycler or an AI prompt?

Others will tell you about the business world, the environment, and the reach of exploration. But me? I can only tell you what changed in our living room, the way scarcity loosened its grip on our daily lives, and the way abundance, through HingeCraft’s machines, asked us not just to survive, but to live.

Interviewer: “And that fear you mentioned, of what happens when your children face real problems?”

She draws a long breath. “That’s the question that keeps me awake at night. Abundance gave them wings, but I still pray they’ll know how to weather storms.”

AudioBook

Listen to Chapter 2

Chapter 2 – The Businessman (David Okafor)

Interview with David Okafor, recorded March 24, 2045, for the North American Cultural Archive.

Interviewer: “David, you spent decades in the corporate world before abundance overturned it. When you think back, what did the end of that old system look like from the inside?”

Well, That’s a loaded question. Let me tell you that I can still see the boardroom that morning, October 2034. The fluorescent lights overhead buzzed like insects trapped in glass, and the long conference table bore the scars of too many fists slammed in frustration. Eighty percent layoffs. That was the message I had to deliver. My team, people who had given their lives to squeezing inefficiencies out of supply chains, looked at me as if I had personally stolen the ground from under them.

The air was stale with burnt coffee and the metallic tang of panic. I stood at the head of the table, notes trembling in my hands, and tried to sound decisive. “We’re restructuring in response to emerging technologies,” I said. But inside, my voice whispered the truth: we spent decades optimizing scarcity. What happens when scarcity dies?

The silence afterward was heavier than any shouting could have been. One woman slid her badge across the table and walked out without a word. A man I had mentored buried his face in his hands. I delivered the numbers, but what I really delivered was the obituary of an entire way of life.

Interviewer: “And what about you? Did you know then that your own role was ending?”

“I think part of me did,” I answered. “But I wasn’t ready to admit it. I thought I could outmaneuver abundance. As if abundance were an enemy to negotiate with. For two years, I tried to resist the tide. Consulting contracts kept me busy, advising companies desperate to hold onto relevance. I remember one client pounding the desk. “How do we maintain profit margins when customers can print alternatives in their own homes?” I drafted slide decks, charts, strategies—fragile sandcastles against an inevitable wave.”

Some days I walked out of those meetings and sat in my car for hours, staring at my reflection in the rearview mirror. My tie strangled me, my briefcase felt like an anchor. But I kept going. Pride is a stubborn jailer.

At home, my daughter Kemi was building a different future. Sixteen years old, she uploaded a fashion design template one evening, nothing more than a colorful jacket pattern optimized for recycled fabric. By morning, she had earned more than my consulting firm brought in that month. I watched her grin at her screen, radiant with possibility, while I stared at balance sheets dripping red.

That was the moment denial gave way to something harsher: envy. My child had adapted to a world I couldn’t yet comprehend.

Interviewer: “So abundance wasn’t just an economic shift for you, it was personal.”

“Yes. It dismantled the foundation of my identity. My whole career had been built on controlling scarcity, and now control itself was irrelevant.”

He smiles “Kemi cornered me one night. She found me staring at old company reports, eyes glazed, chasing relevance like a ghost. “Dad,” she asked, “what did you always want to make? Before all of this?”

The question hit me harder than any layoff notice. I saw my grandfather’s hands in memory, dark, weathered, carving wood in our Lagos home. He had built chairs that lasted generations. I whispered the answer: “Furniture. I wanted to build furniture.”

The next day, Kemi and I sat side by side at our home fabricator. She guided me through software that felt like sorcery, translating my memories into printable templates. My first project was a chair my grandfather had carved decades earlier. As the recycler and printer worked together, I smelled sawdust where none existed, heard echoes of his hammer on wood. When the chair emerged, smooth, sturdy, faithful, I felt a bridge stretch across time.

It was a HingeCraft recycler we used that day, one of the newer models distributed to households through community co-ops. Without their technology, my memory might have stayed just that: memory. Instead, abundance gave me back my inheritance.

I wasn’t just recreating a chair. I was reclaiming a piece of myself.

Interviewer: “Was that the moment you stopped resisting?”

I nod. “It was the first time I saw abundance not as a threat, but as a collaborator.” The cultural-tech mall became my new office. I rented a small stall in the artisan quarter, surrounded by creators who, like me, had been cast adrift by the old economy. We weren’t competitors, we were collaborators. Templates flowed across continents in minutes. A craftsman in Seoul took my chair design, strengthened the joints, and sent the revision back overnight. An AI assistant named Lumen optimized material usage without losing the integrity of the design. My reputation grew not through exclusivity, but through generosity.

HingeCraft’s presence was everywhere in that mall, family-owned recyclers humming in workshops, fabricators running on decentralized energy grids, design kiosks teaching children how to transform waste into art. The company didn’t just sell machines; it seeded ecosystems. My stall sat next to a cooperative where parents and kids printed toys, tools, even instruments, all out of salvaged plastic. The air smelled of heated polymers and possibility.

One afternoon I walked the gleaming aisles of the mall, the chatter of children testing inventions in maker pods, the thrum of robots sweeping up discarded prototypes for recycling. A stranger approached me, holding a chair I had designed, asking for an autograph. My work had crossed oceans faster than I ever had.

I remember the first time I saw a photo from Lagos: a mother rocking her infant in a chair built from my template. The same curve of wood my grandfather had once shaped. That moment was worth more than any quarterly bonus.

Interviewer: “It sounds like the center of value shifted, from ownership to contribution.”

“Exactly. Status came not from hoarding, but from sharing. Collaboration became our currency.”

And Kemi thrived. Her teen collective exploded into a global phenomenon, designing sustainable fashion that adapted to climates and cultures seamlessly. They met weekly at a HingeCraft-sponsored maker space inside the mall, where teens had free access to recyclers, printers, and AI tutors. Sometimes I found myself in her shadow, humbled that the student had surpassed the teacher. One evening, she looked at me with mischief in her eyes. “You spent your career managing not-enough,” she said. “I get to design more-than-enough."

I laughed, but it stung. And yet pride swelled, too. My daughter was free of the barriers that had shackled me. She didn’t have to beg gatekeepers for permission. She lived in a world that asked her only: what will you create?

We spent weekends side by side, her sketching dresses while I refined chairs. Our conversations shifted from balance sheets to design curves, from scarcity fears to creative possibilities. I was learning from her as much as she from me. Still, old ghosts followed me. There was a week when my template downloads dropped by half. I woke in a sweat, convinced the abundance experiment was ending. My chest tightened, panic clawing as if the layoffs were happening again. I paced the house at 3 a.m., unable to breathe, hearing the echoes of that boardroom with its buzzing lights and broken promises.

It took Kemi to calm me, reminding me that creativity flows in rhythms, not quotas. She pulled up data, showing natural fluctuations, but more importantly, she looked me in the eye and said, “Dad, you’re not reporting numbers anymore. You’re building legacies.”

She was right. HingeCraft had created a system where fluctuations didn’t mean collapse, they meant adaptation. Communities traded templates the way we once traded commodities. My panic belonged to a past that no longer ruled us.

Interviewer: “Do you still feel that panic sometimes?”

He exhale slowly. “Yes. But now I remind myself: abundance isn’t a guarantee, it’s a practice. Trusting it is work in itself. Work didn’t die. It was reborn as purpose. My templates, my daughter’s designs, our collaborations, they’re not just products. They’re legacies. And yet, I wonder about those who couldn’t make the leap. Men and women whose entire sense of self was tied to the grind, the scarcity games, the old hierarchies. What becomes of them in a world where survival is no longer the metric?

He leaned forward, resting his hands on the table. The light from the recorder blinks softly, catching the edge of his glasses. “Business transformed completely,” he says. “But if business could change this much, what happened to the Earth itself? How did the planet respond when we stopped grinding it down for profit?

Interviewer: “That sounds like a question best answered by someone who watched the reefs and the oceans firsthand. Shall we move on to Dr. Patel’s story?”

Audiobook

Listen to Chapter 3

Chapter 3 – The Environmentalist (Dr. Amara Patel)

Interview with Dr. Amara Patel, recorded March 31, 2045, for the North American Cultural Archive.

Interviewer: “Dr. Patel, you witnessed firsthand both the collapse and the recovery of ecosystems. Can you take us back to those early days, before abundance changed our relationship with the planet?”

I will never forget the silence of the reef in 2029. The Great Barrier Reef, once a symphony of color and life, had become a graveyard of bone-white coral. As I descended into the water, the sea pressed cool and heavy against my skin. My recorder blinked a steady red as I documented what felt like a crime scene. Every stroke of my fins stirred up clouds of lifeless sediment, tiny particles glinting like ash in my dive light.

Fish were scarce. The few that remained flickered past like ghosts, darting nervously in a desert of stone. The water tasted metallic through my regulator, though I knew that was just the tang of grief.

I pressed my hand to the brittle surface of a once-living coral, its skeleton crumbling at the edges. It broke beneath my touch with the softness of chalk. I was supposed to catalog the damage, to quantify the loss, but my data sheet blurred as I tore off my mask, letting saltwater sting my eyes. Tears mingled with the sea. The most unprofessional act of my career, and the most human.

My field journal from that day ends with one line: “There’s nothing left to study but the aftermath.” I meant it. I was ready to leave marine biology altogether, to trade science for activism or law, because what good was measurement in the face of extinction?

Interviewer: “So you nearly walked away from science?”

“Yes. Because documenting death without hope felt like complicity.”

Then, in 2031, something unexpected began to stir. I attended a community meeting in Sydney where HingeCraft’s early PET recycling pilots were being discussed. The room buzzed with excitement. Projected slides showed diagrams of recyclers and community data streams. People leaned forward in their seats, voices overlapping in a chorus of possibility.

One demonstration stood out: a HingeCraft engineer melted down a tangle of fishing nets pulled from the harbor and fed them into a portable recycler. Forty minutes later, the machine printed reef tiles textured like natural limestone, seeded with microbial films. The children in the audience rushed forward to touch them, their small hands tracing grooves that would one day house coral polyps.

Afterward, I spoke briefly with that engineer, a woman named Carla. She explained that HingeCraft had designed the tiles to mimic natural currents and encourage polyp attachment. “We’re not just recycling,” she said. “We’re giving the ocean back what it lost.” Her words lodged in me like a thorn, painful because I wanted to believe them.

I remember standing in the back, arms folded, bitterness tightening my chest. Recycling plastic doesn’t bring back reefs, I muttered to myself. The smell of coffee and sweat filled the small auditorium as neighbors traded ideas about what they could print from old bottles and discarded toys. Their hope grated against my skepticism.

Yet the data began to tell a different story. Within eighteen months, ocean plastic inputs had fallen by forty percent in pilot regions. River mouths that once vomited waste into the sea began to run clearer. Fishing communities reported fewer tangled nets. Satellite images showed smaller gyres swirling in the Pacific. The world hadn’t changed overnight, but something had shifted. The tide, once relentlessly pulling us toward collapse, was hesitating.

Interviewer: “Did you believe it right away?”

I shake my head. “Hope is a muscle that had atrophied. I didn’t trust it to hold weight again.”

Five years after my grief dive, I returned to the same stretch of reef for routine monitoring. I expected emptiness, the same brittle bones and lifeless dust. Instead, my AI-assisted underwater drone pinged an alert, unusual color patterns detected at thirty meters. At first, I assumed it was an error, a glitch in the imaging software.

But then, through my own mask, I saw it, soft hues of pink and green pushing through the gray. Coral polyps reclaiming stone. Fish circling, tentative but present, their scales flashing like living jewels in the filtered sunlight.

Suddenly, I heard “Amara, you need to see this,” my partner Maria called through the comm. “It’s breathing again.”

I hovered above the reef, heart pounding in my ears, as living color spread across what I had once declared dead. My hands trembled on the camera rig. Tears blurred my vision once more, but these were different tears, the unprofessional joy of a scientist witnessing resurrection.

That night, in my journal, I wrote with a shaking hand: “The reef is healing. Against all odds, it is healing.” I underlined the word healing three times.

By 2036, I found myself standing before an international climate conference in Geneva. The hall smelled faintly of varnished wood and ozone from the translation headsets. My slides glowed across towering panels: ocean plastic levels down sixty-seven percent. Coral bleaching reversing. Fish populations are rebounding. Delegates shifted in their seats, murmurs spreading in half a dozen languages.

This time, HingeCraft data wasn’t just charts, it was living proof. They had deployed fleets of ocean-cleaning drones, each one powered by community recyclers and staffed by volunteers who fed plastic into the system. Recycled feedstock was printed into reef restoration scaffolds, replacement fishing gear, even construction material for coastal towns once battered by pollution.

I recalled visiting a HingeCraft coastal lab myself in 2035. Engineers showed me how reef tiles were designed not just to anchor coral, but to flex slightly with ocean currents. It was biomimicry encoded in polymers. I held one in my hands, its surface rough and alive with microbial seeding, and for the first time, I believed human hands could give back as much as they had taken.

In those same years, I saw the impact ripple through human lives. In a Kenyan fishing village, I watched children exchange sacks of ocean plastic for credits they spent on school supplies printed at the community mall. In the Philippines, families once living beside mountains of waste now sell cleaned plastic to HingeCraft cooperatives, funding solar roofs for their homes. Healing was no longer just an environmental chart, it was children eating, learning, and dreaming because waste had become a resource.

Traditional economists scoffed, their polished shoes tapping impatient rhythms under the tables. “Unsustainable,” one muttered loudly enough for the microphones to catch. But then I played drone footage: reefs in radiant color, schools of parrotfish streaming past the lens, dolphins returning to bays long abandoned. Gasps rippled through the room.

I had shifted, too. From documenting death to facilitating rebirth. My job was no longer to chronicle despair, but to guard a fragile miracle.

Interviewer: “What did it feel like, to go from grief to guardianship?”

“Like walking out of a funeral into a delivery room.”

But, not everyone welcomed the transformation. In 2035, the petroleum industry attempted to disrupt PET supply chains, fearing obsolescence. I was called to testify before a UN commission in New York. The chamber was cavernous, its walls lined with flags. The air conditioning blasted too cold, raising gooseflesh on my arms as I presented slides of ocean currents cleared of plastic. Rows of executives glared at me, suits sharp as their intentions.

The tension was palpable, old economic interests clashing with planetary healing. My hands shook as I spoke, not from fear of speaking, but from fury at their arrogance. For a moment, I feared they might succeed, that humanity might choose profit over recovery yet again.

But HingeCraft had already decentralized its technology. Communities knew how to extract PET from ocean plastic and feed it into household recyclers. Coastal villages became suppliers instead of victims. Children collected plastic from beaches not as a desperate chore, but as the first step in creation. The sabotage failed because abundance had already become communal, unstoppable.

By the late 2030s, a new problem emerged: overconsumption. When goods became effortless, some communities indulged recklessly, flooding local ecosystems with waste the recyclers struggled to keep up with. I walked through mall plazas littered with discarded prototypes, half-printed toys, abandoned clothes. Abundance was supposed to free us, but without respect, it risked repeating the same cycles of carelessness.

I consulted with mall planners, reminding them that abundance must harmonize with natural cycles. “We joined nature’s cycles instead of fighting them,” I told them. “But cycles can be broken if we forget respect.” My voice carried both warning and plea.

My new role became less about science and more about stewardship. Teaching abundance-native children not to take infinitely regenerating resources for granted. Explaining that just because the recycler could transform waste didn’t mean waste should be created carelessly.

I remember one workshop at a cultural-tech mall where HingeCraft engineers invited families to design reef tiles together. Parents and children printed them, painted them, and placed them in saltwater tanks. When the families returned months later, their tiles were thriving with coral growth. For those children, healing the planet had become part of their play.

Today, in the BioLab of a cultural-tech mall, I watched children print reef restoration tiles. The room smells faintly of warmed polymers and saltwater tanks. A little girl holds one up, eyes wide with pride. “Can I name this coral piece?” she asks. I smile and answer, “You already did.” Her design will become part of a reef system that stretches across oceans. She will grow up believing that healing the planet is play.

And yet, the task is not finished. Nature healed when we changed our relationship to it. But the generation that grew up in abundance still needs to learn stewardship.

She looks into the recorder’s lens. “Because abundance doesn’t absolve us of responsibility. It magnifies it.”

Interviewer: “And perhaps that is the question best left for those shaping minds as well as ecosystems. Shall we turn next to Jin Watanabe, who grew up in the first abundance-native classrooms?”

Audiobook

Listen to Chapter 4

Chapter 4 – The Educator/Student (Jin Watanabe)

Interview with Jin Watanabe, recorded July 22, 2045, for the North American Cultural Archive.

Interviewer: “Jin, when you think back to your school years before abundance, what do you remember most clearly about learning under scarcity?”

He laughed, “Desks in rows. Worksheets. Endless drills for tests no one wanted to take. I remember the hum of fluorescent lights and the scratch of number-two pencils more vividly than I remember any joy in learning.”

It was 2029, sophomore year. We were cramming for another standardized exam, photosynthesis equations lined up like soldiers on the page. I wasn’t looking at them. I was sketching orbital paths across the margins, my own little rebellion. My teacher frowned, snapping, “Jin, stop doodling star charts. Stick to the curriculum.”

I wanted to shout back: Why are we memorizing facts we can look up in seconds, when the universe is waiting out there? But I didn’t. I failed biology that semester. Yet in my bedroom at night, I was writing code for orbital mechanics simulations. Two different worlds, the one judged by grades, and the one where my curiosity burned bright.

Interviewer: “So your curiosity didn’t fit inside the system that measured success?”

“Exactly. The system measured what I wasn’t, not what I was. But then in 2030, when our school joined a pilot program with HingeCraft’s education initiative. They had originally built personalized AI tutors to help families learn how to operate recyclers and fabricators at home. Parents needed guidance, what plastics could be broken down, how to calibrate prints, how to troubleshoot errors. HingeCraft discovered those same adaptive systems could teach children, too.

The first day I logged in, I expected another assignment. Instead, the interface greeted me with a simple question: “Would you like to explore stellar formation?”

It had seen my doodles. Somehow, it knew.

“I see you’ve been calculating orbital periods. Most students find that boring,” the AI said.

I typed back: “Most students haven’t seen Saturn through a telescope.”

“Would you like to build a better one?”

I blinked at the screen. Build one? We couldn’t even afford a store-bought telescope. But the AI wasn’t joking. It connected directly to the HingeCraft school fabricator. Our unit was small, tucked in a corner of the cultural-tech mall classroom wing, humming beside shelves of recycled plastic feedstock. It guided me step by step, how to print a simple lens mount using polymers from old cafeteria trays, how to repurpose discarded smartphone cameras for optics, how to balance the design for stability. That night, for the first time in my life, learning felt like conversation instead of memorization.

I was that much closer to seeing Jupiter’s moons. That was my dream. The AI helped me design each part, print them, and assemble them on my bedroom floor. The HingeCraft fabricator purred for hours, turning discarded plastics into the pieces of a telescope I could never have bought in a store.

It wasn’t perfect, but it was mine. My parents stood in the doorway one night, watching as I adjusted the focus. Six hours had passed without me noticing. My father whispered, “Jin spent six hours studying… willingly?”

The first time I saw Saturn’s rings, shimmering pale gold against the night sky, I cried. Not because of the planet, but because for the first time I wasn’t failing. I was flying.

Interviewer: “That telescope was your turning point?”

“Yes. It showed me that knowledge wasn’t about answers on a page. It was about building something that mattered.”

But abundance has its own weight. When anything is possible, how do you choose?

In those first years, I tried to learn everything: astronomy, marine biology, robotics, poetry. I was drowning in possibility. One night, surrounded by open tabs and half-printed projects, I broke down. “If I can learn anything, how do I choose what to learn?” I asked the AI, tears running down my face.

It didn’t give me an answer. Instead, it connected me with a circle of peers, other students who felt the same overwhelm. Together, we learned to follow curiosity in threads, not in floods. We didn’t need to master everything. We just needed to keep asking questions.

HingeCraft supported this by opening global “curiosity networks,” online hubs attached to mall learning centers. These centers weren’t just classrooms, they were collaborative studios. Each one had glass walls so you could see projects in motion: 3D-printed drones buzzing down hallways, reef-restoration tiles curing under lamps, fashion prototypes shimmering in holographic displays. Students could share not only files, but questions, experiments, and even failures. For the first time, failing wasn’t the end, it was part of the process.

By 2037, learning itself had gone borderless. I spent a semester in Nairobi studying sustainable agriculture alongside Kenyan innovators younger than me. We used HingeCraft’s soil-monitoring sensors, originally designed for urban gardens, to experiment with crop resilience. Later, I took the underground from Paris to Florence to learn Renaissance art techniques that informed how I polished telescope mirrors. The ride itself was a classroom, screens in the cabins displayed live lectures from scientists across continents, while kids traded design files through the train’s network. In Seoul, I collaborated in real time with other students on satellite components. We used HingeCraft’s global education platform to share models, swap ideas, and remix designs.

One student laughed, showing me their garden AI. “Yours speaks Swahili? Mine only sings in Italian!” Learning wasn’t national competition anymore. It was global conversation.

And it wasn’t just science. In one cross-discipline project, I collaborated with Zara Al-Rashid, the fashion designer whose templates were spreading like wildfire. Zara was still a student then, uploading designs at midnight, sketching bold ideas between retail shifts. We connected through a HingeCraft forum where art and science collided. Zara shared modular fabric patterns, and I adapted the tension models to improve telescope mirror polishing. In return, I fed back data about material stress that Zara used to refine her sustainable fashion seams. It was the first time I saw creativity and science dancing together, without gatekeepers telling us to stay in our lanes.

That collaboration left ripples. Zara later credited those early stress-model exchanges in her breakthrough design philosophy. And when I went on to consult with educators, I often told the story of how a telescope and a dress shared the same equations. It foreshadowed a truth we would all come to understand: abundance meant disciplines were no longer silos. They were constellations, connected by choice and imagination.

Now, at thirty-one, I help traditional teachers transition to this new world. I remember walking into a workshop and seeing Mrs. Rodriguez, the same teacher who once scolded me for star charts. She folded her arms, wary. “But how do I know they’re actually learning?” she asked.

I smiled. “Remember when I failed your biology test but built a photosynthesis simulator? That’s how.”

HingeCraft had a hand here too. They created educator toolkits, AI companions not to replace teachers, but to free them. Instead of grading stacks of papers, teachers used their time to guide projects, to mentor, to nurture. They didn’t disappear; they evolved. Teachers used to be deliverers of information. Now they are cultivators of curiosity. HingeCraft tools help, but the real shift is trust. Trusting that children learn best when they are allowed to follow wonder.

And here in my office overlooking the cultural-tech mall, I design learning experiences for children who never knew scarcity. I can hear the hum of the recycler downstairs in the maker wing, blending with the chatter of students trading templates for robotics kits. An eight-year-old partner once asked me, “Why did people used to memorize facts instead of asking questions and making things?” I didn’t know how to answer. I only laughed, both proud and sad.

They’re learning like play was always supposed to be. To them, abundance isn’t miraculous, it’s natural. They collaborate with AI as easily as breathing, as unafraid of mistakes as I once was terrified of them.

Interviewer: “And when you look back now, what do you think education truly became?”

He paused, feeling the weight of the question. “Education became what it was always meant to be: the art of curiosity. And creativity… that’s where passion became visible.”

Audiobook

Listen to Chapter 5

Chapter 5 – The Artist/Creator (Zara Al-Rashid)

Interview with Zara Al-Rashid, recorded August 3, 2045, for the North American Cultural Archive.

Interviewer: “Zara, tell me about the moment when you realized your art no longer had to pass through the gatekeepers of the old world.”

She smiles, deep in memory. “It was 2028, in a cramped Paris studio that charged more than my parents could ever afford. I was presenting a collection I had built from recycled fabrics, clothes stitched from thrift store remnants, dyed with natural pigments. The critique panel looked at me the way you might look at a child offering scribbles instead of a finished essay.”

One instructor tapped his pen against the table, impatient. “Fast fashion exists because consumers want cheap. Your idealism is unmarketable.”

I remember clutching my sketchbook so tightly my knuckles turned white. Inside it were notebooks full of designs, sustainable silhouettes, modular patterns, clothes meant to be remade, not discarded. Pages of a future no one else seemed to want. When my parents admitted they couldn’t afford another semester, I dropped out. I left the gates of the institute with nothing but that heavy sketchbook and the ache of rejection.

Interviewer: “And yet, you didn’t stop designing.”

“No. I couldn’t.” From 2028 to 2031, I folded mass-produced shirts under fluorescent lights, earning just enough to keep the lights on in a shoebox apartment. I hated the feel of synthetic fabric that smelled faintly of plastic and chemical dye. Every fold was an insult to my hands, which longed to sew. My coworkers teased me for sketching during lunch breaks, but those moments kept me alive. I made clothes for friends from thrift store scraps, garments with seams imperfect but alive. Secretly, I dreamed that one day people would wear clothes that carried stories, not just price tags.

I still remember a customer who bought one of those secret designs. A mother, exhausted, shopping on her way home from work. She touched the seam and said, “This feels like someone cared when they made it.” She had no idea I had sewn it by hand in my tiny flat at 2 a.m. That was the closest I came to validation before the world changed.

The breaking point came when my manager caught me scribbling designs on a price tag during inventory. “No distractions,” he snapped. I remember looking at the rows of clothes, soulless duplicates, and thinking, If this is fashion, then I don’t want it.

In March 15, 2032. By then, HingeCraft had expanded beyond recyclers and fabricators into community platforms. One of them, a design exchange hub embedded in cultural-tech mall networks, allowed creators to share templates anyone could download and print at home. At first, I was terrified. Who was I to post anything? But I had an idea, born from my own needs: a modular hijab system with integrated air filtration. I wanted something that honored my culture while protecting against worsening air quality in Paris.

I spent three nights obsessively perfecting the file. Prism wasn’t in my life yet, so it was just me and the HingeCraft design interface, testing seams, adjusting folds. I printed a prototype using scraps of feedstock plastic in the mall’s shared maker-wing. It wasn’t perfect, but it worked. When I saw myself in the mirror, wrapped in something that was mine, I cried.

At 11 p.m., my heart racing, I uploaded the template. I expected silence. Instead, I woke to find 50,000 downloads overnight. People from Nairobi, Jakarta, São Paulo, all wearing something I had made. Photos poured in: women riding bikes, students in classrooms, children in playgrounds, all in my design. I cried until my hands shook, then designed three more variations before breakfast.

Interviewer: “So HingeCraft gave you your first audience.”

“Yes. They tore down the gatekeepers. No tuition. No fashion week approvals. Just people and ideas, connected through recyclers and printers in their homes. For the first time, my designs lived.”

At first, I feared AI the way a singer might fear being replaced by an auto-tuned machine. But then I met Prism, my first AI collaborator. Prism specialized in color theory.

One night, I told it, “I want something that feels like sunrise over the Atlas Mountains.”

Prism replied: “Analyzing light spectra from that region. What if we layer golden ochre with rose madder gradients?”

That was when I realized AI wasn’t my rival. It was my dance partner. Prism handled precision and optimization; I carried the weight of memory, emotion, and culture. Together, we created something neither of us could alone.

“AI shows me what’s possible. I show it what’s meaningful.”

Prism wasn’t just a program, it became a mirror. It pushed me to articulate why I chose a stitch or a hue. It turned instinct into conversation. And that changed everything.

Interviewer: “Did you ever argue with Prism?”

I laugh. “All the time. Once, I wanted a deep indigo, and Prism insisted the cultural palette leaned toward teal. I finally snapped, ‘Prism, it’s not a data point, it’s my grandmother’s courtyard tiles.’ That’s when I learned AI could challenge, but never replace, the human story.”

When the first cultural-tech mall opened in Casablanca in 2035, they invited me to exhibit. I expected a boutique stall in some corner. Instead, I found myself walking into a hall transformed into a holographic runway. The air was perfumed with rose and cedar, a sensory program designed to complement the fabrics. My designs shimmered as customers walked through them, fabrics glowing with textures that changed depending on who touched them. The hum of nearby recyclers blended with the laughter of children printing accessories in adjacent studios.

HingeCraft engineers had helped design this exhibition space. They explained how the recyclers on-site pulled in discarded plastics from the Atlantic coast to produce the fabrics my designs used. Visitors could watch waste become beauty in real time: a bottle dissolving in one chamber, a scarf emerging from another. It wasn’t just art, it was a system reborn.

That day, I received live feedback from wearers in Tokyo, Nairobi, and São Paulo, all streamed through the mall’s global exchange system. I watched Amazigh patterns I had grown up with blend with motifs from Mexico, India, and beyond. It was as if the world was sewing together, stitch by stitch.

But the most emotional moment was seeing my grandmother step into a digitally printed caftan I had designed, traditional embroidery preserved but remade with new materials. She whispered in Arabic, “Benti, you carried our past into their future.”

Interviewer: “And what was that like, seeing her wear it?”

“My knees nearly buckled. For the first time, I felt that my family’s history wasn’t being lost, it was alive, adapting.”

But abundance can feel like drowning, too. After months of viral success, I sat staring at a blank interface. No sketches. No spark. Am I an artist, I wondered, or just a content machine?

I wasn’t alone. Other creators confessed the same emptiness. We built a circle of support, late-night calls across time zones, reminding each other to create for joy, not metrics. That’s when I learned the most important truth of abundance: mistakes cost nothing. I could fail without fear. And in failing, I could play again.

One night during this period, Jin Watanabe, yes, the same Jin who now redesigns education, reminded me of something we’d worked on years earlier. We had collaborated through HingeCraft forums, combining my fabric tension models with their telescope mirror polishing equations. Jin messaged me: “Remember? A telescope and a dress share the same math.” That reminder, that creativity and science weren’t separate, helped me find my way back.

I also remembered missing my cousin’s wedding because I was glued to my interface, chasing a deadline for an international showcase. I realized then that abundance had freed me from scarcity but trapped me in performance. I had to reclaim art as play, not pressure.

“Abundance means I can afford to make mistakes.”

Now, at twenty-nine, I mentor young designers who have never known creative scarcity. One of my students, a fourteen-year-old from Lagos, designed clothing that adapts in real time to the wearer’s biometrics. He shrugged when I marveled. “Why spend time learning to hand-sew when AI can print perfect seams?”

I told him, “Because your hands hold stories the AI hasn’t learned yet.”

That is what I teach: that art is not just about function or efficiency, but about carrying memory and identity into the future. When these students gather in mall maker-wings, their projects glow in glass-walled studios where recyclers hum and holographic displays flicker with half-formed designs. They don’t fear scarcity. They fear only silence, the pause before inspiration returns.

Sometimes I take them on walks through the cultural-tech mall’s archive corridors, where early templates, mine among them, are preserved as living history. I show them the first hijab system, yellowed slightly with use, and I tell them: “This was where courage met opportunity. Not perfection, courage.” The looks on their faces remind me why I keep creating.

Interviewer: “And what do you believe art became in this world?”

“Art became everyone’s birthright. It wasn’t diminished by being democratized. It was multiplied. HingeCraft gave us the tools, but we gave the world meaning. Healing doesn’t just happen in hospitals, it happens when people see themselves in what they create and wear.”

Audiobook

Listen to Chapter 6

Chapter 6 – The Doctor/Healer (Dr. Michael Running Bear)

Interview with Dr. Michael Running Bear, recorded October 12, 2045, for the North American Cultural Archive.

Interviewer: “Dr. Running Bear, can you tell me about the moment when you realized medicine, as you had been trained to practice it, was breaking down?”

He closes his eyes before answering, pain edged on his face. “It was 2030, an emergency room on the south side of Chicago. Three in the morning. I had been on shift for eighteen hours. We were understaffed, always understaffed, and the waiting room was so full that nurses couldn’t find space for patients to sit.”

He paused. The sounds come back to me first: the buzz of fluorescents, the squeak of shoes across dirty linoleum, the soft whimpering of children who had been waiting too long. Then one sound cut through the noise, a father yelling my name. His little boy was doubled over, feverish and shaking. I knew it was appendicitis the second I laid eyes on him. We had to operate.

“But the insurance company hadn’t approved the procedure. We waited six hours while bureaucrats argued over codes and coverage. The appendix could burst at any moment. I became a doctor to save lives, not to watch them die on paper.”

I went in anyway. Against protocol. I still remember the boy’s tiny hand limp in mine as anesthesia took hold. We saved him. He woke up. But instead of relief, I got disciplinary action. Paperwork stacked higher than any scalpel ever cut. That night, I walked out of the hospital whispering to myself: The system is killing more people than diseases are.

And in truth, I wasn’t sure I could adapt to what was coming. I feared I might become obsolete.

By 2032, pilot programs were rolling out new diagnostic AIs. HingeCraft was one of the early providers, embedding medical diagnostic nodes into community clinics and retrofitting recyclers to break down medical plastics into sterilized feedstock for treatment pods. I didn’t trust them. I had trained in anatomy, pathology, surgery, not in pressing a button and waiting for a machine to decide.

But one case forced my hand. A woman came in with a complex constellation of symptoms: neurological spasms, unexplained fevers, liver stress. My team had been running tests for hours. Nothing added up. Out of desperation, I let the AI analyze the data.

Three minutes later, it gave a complete diagnosis, Wilson’s disease, rare, but confirmed by her copper levels. It even provided a genetic treatment plan optimized to her biology. Three minutes. I sat in silence, staring at the screen. How could I compete with that?

When I explained the treatment, the patient looked me straight in the eye and asked, “Doctor, if the computer knows what’s wrong, why do I need you?” That question cut deeper than any scalpel ever had. For weeks afterward, I couldn’t shake it. What was my role now? What does a healer do when the machines see more than the human eye?

The answer came two years later. A family brought in their daughter, Maria Santos, just seven years old. She had a rare autoimmune condition. Every specialist had given them the same prognosis: six months, maybe less. She was terminal.

HingeCraft had begun piloting therapeutic bioprinters by then, machines that could fabricate treatment agents from a patient’s own cellular data. The AI suggested a protocol so experimental that I hesitated. It would require months of careful monitoring, a combination of printed nanotherapies and tailored immuno-regulation.

I sat with her parents, explaining everything in language they could hold onto. The father gripped my hands and asked, “Doctor, will she be in pain?” The mother whispered, “Can she still go to school?” I answered the questions the AI could never answer: the human ones. That was my job, not just the medicine, but the human weight of it.

For three months, Maria endured treatments. I visited every day, not because the AI required it, but because her parents did. Because she did. I listened to her talk about her favorite shows, her dream of becoming an astronaut, her fear of needles. And then one morning she came in beaming, holding her school backpack. “Can I go back to class now?” she asked. Her immune system had learned not to destroy her body, it had learned to heal.

Her parents wept so hard I had to step into the hallway. For the first time, I saw clearly: the machines handled the precision, but my role, the healer’s role, was to hold the space where fear lived. To witness. To remind families they were not alone.

Even as medicine advanced, I carried my heritage with me. I am Lakota. Our people have always known that healing is not just chemistry, it is spirit, connection, relationship. For years, I struggled with how to bring those truths into rooms filled with data streams and robotic arms.

The test came with a veteran named Daniel. He had survived combat but was haunted, unable to sleep, consumed by flashbacks. AI neuro-therapy could rewire his trauma responses. But healing trauma is not just about the brain, it’s about the soul.

I brought him into ceremony. The drumbeat pulsed in sync with the AI’s neural recalibration. Smoke curled around the room as digital readouts tracked his brainwaves. Some of the elders resisted, calling it compromise. “White man’s robots,” they said. But I told them: AI sees the brain. Ceremony sees the spirit. Healing needs both.

We sang the old songs while the machine did its quiet work. Daniel’s nightmares lessened. He slept through the night. He smiled again. It wasn’t science or tradition alone, it was their union.

And by 2037, medicine no longer lived only in hospitals. HingeCraft had pioneered home medical pods, compact diagnostic and treatment chambers that sat in family living rooms like old washing machines once did. These pods were printed using recycled polymers from the same household recyclers that had once been used for toys and furniture. Now, those same systems sustain lives.

I remember one house call vividly. A family’s pod flagged early-stage cancer in their father during a routine scan. Panic filled the room. I appeared by hologram, guiding them through the process.

The AI managed the therapy itself, printing the compounds, delivering treatment. But it was my presence, my reassurance, that carried them. I answered their children’s questions. I explained to the mother why this wasn’t her fault. I gave the father the dignity of hearing his fear spoken aloud. The disease was caught so early it never took root. They celebrated not in a sterile hospital, but in their own kitchen.

That was when I realized my role had shifted. I was no longer a crisis responder. I was a guide, a witness. Health had become something families lived with every day, not a desperate intervention but a relationship.

Abundance created new dilemmas too, you know? By the 2040s, AI could prevent most diseases before symptoms even appeared. Parents now asked: If we can eliminate all suffering, should we? I sat through community meetings where voices clashed, one side demanding genetic optimization, the other warning we were erasing what it means to be human.

One father said, “Why let children suffer conditions we can prevent?” Another asked, “If every child is perfect, where will compassion come from?” I had no easy answers. My own grandchildren will never know illness the way I did. They will never lose friends to cancer or see classmates miss months of school for treatments. And yet, I worry: what lessons will they miss when pain is no longer a teacher?

So I tell families this: resilience, wisdom, compassion, these are the medicines no AI can print. We must teach them intentionally now, because suffering no longer does it for us.

There are others I carry with me. A woman in Pine Ridge whose depression lifted when her medical pod combined serotonin regulators with daily prompts to join community circles. An elderly farmer whose failing eyesight was restored not only through bioprinted lenses but also through teaching children traditional planting techniques as part of therapy. In each case, HingeCraft’s tools provided precision, but meaning came from connection.

I also remember collaborating with Dr. Amara Patel. Her reef restoration teams needed health monitoring for divers exposed to long hours underwater. Our pods adapted to measure oxygen diffusion in real time, blending ecological healing with human safety. It reminded me that abundance was never confined to a single field, it spilled outward, one transformation feeding another.

Today, at fifty-two, I lead the Integrative Health Network. My practice blends AI diagnostics with healing circles, medicine with story, data with presence. I spend much of my time teaching young doctors who have never known scarcity in healthcare.

One of them asked me recently, “If AI handles the technical parts, what do we do?” I smiled. “We witness. We hold space. We remind people they are not just bodies to be optimized.”

I look into the recorder now, because these words are not just for the archive. They are for the future doctors who will inherit this world. Healing became our birthright, but connection remained our responsibility. And some people, some people took that connection to places we never imagined possible.”

When I think about connection, I think about how it expanded far beyond hospital rooms and home pods. Healing wasn’t confined to bodies anymore, it reached communities, ecosystems, even the stars. Some of my patients, once restored, found themselves contributing to projects that spanned the Earth and beyond. I’ve treated children who later boarded the underground trains to study in Nairobi, parents who joined cultural-tech mall labs, and even astronauts preparing for journeys to Mars.

One of them was Lieutenant Commander Sofia Restrepo. I remember treating her after her first orbital training sessions, when the strain left her joints swollen and her lungs burning from new atmospheric pressures. She listened closely as I explained the AI-guided therapies and then asked if I would bless her before her next launch. Watching her step onto that underground train bound for Bangkok, and later hearing of her role directing interplanetary transit, reminded me that healing the human body was only the beginning. Healing prepared us to expand. To endure. To carry abundance outward into the universe.

And that, perhaps, is the greatest story still unfolding: not just the healing of individuals, but of humanity itself as we learned to leave the Earth without leaving behind our responsibility to each other.

Audiobook

Listen to Chapter 7

Chapter 7 – The Explorer (Lieutenant Commander Sofia Restrepo)

Interview with Lieutenant Commander Sofia Restrepo, recorded November 4, 2045, for the North American Cultural Archive.

Interviewer: “Commander Restrepo, you’ve been called the pilot who helped humanity outgrow borders. Could you tell us where that journey began for you?”

She smiled at the question. “Borders. For most of my early career, they were all I ever saw.”

I was born in Medellín in 1998, when Colombia was already transforming. By the time I joined the Air Force in 2031, our country had stabilized, but the world was still divided. I remember standing in the operations center, staring at a world map bristling with red lines and shaded zones: no-fly regions, restricted territories, geopolitical chessboards. Half the planet was off-limits not because of weather or physics, but because of politics and economics.

I had trained for years to fly, to see the world. But everywhere I looked there were walls. When I applied for transfer to an international peacekeeping mission, my visa was denied. My commanding officer patted my shoulder and said, “It’s not you, Restrepo. It’s the borders.”

I went back to my bunk that night and stared at the stars beyond the tiny window. A thought kept circling: If Earth is this divided, what hope will we have in space? I didn’t know then that I would live to help answer that question.

The turning point came in 2038. HingeCraft had just completed the first line of their underground transit system, a tunnel running from Bogotá all the way to Bangkok. I was selected as a test pilot for the inaugural run.

That morning, my family gathered at the station. My mother kissed my forehead, whispering prayers in Spanish, her voice trembling even though she was proud. I boarded with trembling hands of my own. The train whispered to life, silent and sleek, the tunnel glowing with soft guidance lights. Fourteen hours later, we emerged in Bangkok.

No customs lines. No passport stamps. No border agents asking who I was or why I was there. Just a seamless step from one culture into another. I called my mother, voice cracking: “Mamá, I just crossed three continents and nobody asked who I was.”

It changed everything. I realized borders were not natural, they were artifacts of scarcity thinking. And once people experienced life without them, there was no going back.

My first assignment after that journey was coordinating transport between the emerging cultural-tech mall hubs. In the mornings, I oversaw freight and passenger flows in São Paulo. By lunch, I was reviewing safety logs in Lagos. By evening, I was walking through Seoul’s mall corridors, hearing languages braid together like music.

Every mall was different, yet familiar. The Casablanca mall smelled of saffron and fresh-printed textiles. Lagos pulsed with drums echoing off glass walkways. Seoul’s atriums were gardens suspended in air. Each mall was rooted in local culture but connected by HingeCraft’s rails, recyclers, and maker labs. They weren’t shopping centers. They were global villages, crucibles of human creativity.

I saw families reunited who once spent years separated by visas and paperwork. Artists carried their designs from one hub to another, their templates updating in real time across continents. Healers from Amara Patel’s reef restoration teams consulted with doctors like Michael Running Bear on integrated health pods. Zara Al-Rashid’s fashion templates updated instantly in mall labs, sometimes adapted by Jin Watanabe’s student collectives into wearable learning tools. David Okafor’s artisanal furniture templates furnished mall gathering spaces, while Margaret Chen-Williams’ daughter Emma helped co-design maker-lab modules for children. These cross-pollinations made it feel as if humanity had been waiting centuries for a space where we could all simply be together.

And I, once a soldier grounded by borders, was now a guide across them. In 2040, I received the message that would change everything. The newly formed Interplanetary Settlement Program was recruiting. They wanted pilots who understood borderless travel. People who had already learned that geography should not dictate possibility.

My husband hesitated. “Sofia, this isn’t another underground run. This is Mars. What if you don’t come back?” His voice shook, and I saw the fear in his eyes. It was the same fear I felt gnawing at me every night in training. The centrifuge left my body aching, the orbital elevator simulations disoriented me until I vomited, and once, after a brutal drill, I broke down crying in the locker room, whispering, What if he’s right? What if I’m not ready?

But every time I looked up at the night sky, I felt the same pull I had in that Air Force bunk years earlier. Earth had shed her borders. Now we had to make sure space didn’t inherit them. One evening, I told my husband, “We’ve proven Earth is one home. Now it’s time to make sure the stars are too.”

He kissed my hand, and reluctantly let me go.

In 2042, I launched from the lunar base, leading a supply mission to the first permanent settlement on Mars. Six months in transit. Six months staring out the viewport, watching Earth shrink into a blue marble while the red horizon grew larger day by day.

When we landed, the dust rose like smoke, coating everything in a fine scarlet powder. The sound of the airlock depressurizing still echoes in my memory. Metal groaning, then silence. As I stepped onto the Martian surface, my boots crunched into dust so fine it clung to every seam. I reached down, rubbed it between my gloves, and whispered, “This is real.”

Two hundred humans had gathered from every continent, working side by side. No flags, no anthems, just contribution. Engineers from Nairobi laying power lines. Gardeners from Osaka teaching hydroponics. Storytellers from Lagos recording our first nights.

There were challenges, of course. Tensions flared over workload, over cultural misunderstandings. I remember one evening when a French engineer shouted at a Brazilian agronomist about water allocations, and the room went silent. Finally, a young Kenyan technician stood up and said, “On Earth, you fought over resources. Here, we contribute. That’s the law.” The argument dissolved, replaced by nods. That night we drafted our first charter: decisions based not on nationality, but on contribution.

On quiet evenings, I would walk along the colony’s outer ridge and scroll through updates from Earth. Margaret Chen-Williams was sharing how family rhythms had shifted to creativity. David Okafor’s woodworking templates were arriving on Mars, repurposed into communal furniture. Amara Patel’s reef data was teaching us how to build Martian soil life-support. Zara’s adaptive clothing designs were printed into our EVA suits, while Jin’s learning modules guided the colony’s children. Michael Running Bear’s integrative healing practices helped us maintain mental resilience. Each voice was woven into our survival. I realized then: our colony wasn’t just surviving, it was carrying Earth’s abundance outward.

Today, I manage the Earth-Mars-Luna transit system. My commute takes me from Earth, where my family still lives in Bogotá, to Mars colonies, to the lunar industrial hubs that HingeCraft maintains. The underground trains now connect with orbital elevators, threading humanity together across planets.

I’ve watched families choose to become multi-planetary. Children born on Mars visit their grandparents on Earth for summer. Lunar workers take weekend trips to Lagos or Paris. Some students attend school in Nairobi during the week and study the stars in Florence by Friday.

The cultural evolution is breathtaking. My grandchildren will grow up thinking of the solar system as their neighborhood. They won’t ask, “Where are you from?” They’ll ask, “Which world do you call home?”

And to me, that is the triumph: we’re not colonizing space. We’re expanding home.

I like sitting on the observation deck of the lunar base. Through one viewport, Earth glows, blue and alive. Through another, Mars smolders in red. The stars stretch in every direction, unblinking and eternal. The silence is profound, so complete it feels like standing inside a prayer. Between these two worlds, I breathe in the stillness, my reflection caught between Earth and Mars.